Don’t Pull: The Parable of the Weeds and Wheat

Matthew 13:24-30

Published in the Anglican Digest, Fall 2018

My grandmother preached against the weeds. She was one of the first women ordained in the United Methodist Church in the late 1960’s. From the pulpit she preached peace and grace and I can still hear her sweet voice and see her in her black robe when she spoke in church. In her home, around the kitchen, however, she was known to preach more judgement. She was still sweet and her words still full of grace for her grandchildren but it was not uncommon to hear the harsh words about how God would “burn up those sinners.” Her own childhood among Brethren Christians had taught her, in vivid imagery, that a fiery furnace awaits which shall consume the wicked “weeds” of this world but that the “wheat” would be spared. Sitting around her kitchen table, listening to her deep, family preaching, I knew I didn’t want to be a weed.

The parable of the weeds and the wheat from Matthew’s thirteenth chapter is often taught that way. In the parable’s explanation just a few verses on Jesus tells his disciples that the weeds are the wicked ones who have been sown by the devil and will ultimately be cast in the fiery furnace. This explanation by Jesus himself seems to reinforce my grandmother’s heavy judgement preaching. But by focusing on this explanation we can easily miss the textures and the deeper lessons that Jesus’ parables often meant to provide.

Pace to my grandmother’s kitchen table teaching, and centuries of Christian preaching judgement with this parable, we all often have a tendency to want to reduce parables to an easily understood analogy or metaphor. It’s our human nature to want to know what the basic lesson is, to reach for the bottom line or find the neatly packaged guidance for our understanding and behavior and then practice following it through as best we can.

A parable by it’s nature, however, is not meant to be so easy to reduce. The Welsh theologian C.H. Dodd, himself no stranger to the effects of powerful story making, helps us to discover that, “At its simplest, the parable is a metaphor or simile drawn from nature or common life, arresting the hearer by its vividness or strangeness, and leaving the mind in sufficient doubt to its precise application to tease the mind into active thought.”

“Sufficient doubt” as to “precise application” allows us the poetic room to ruminate more broadly on Jesus’ parable of weeds and wheat without rushing to categories of judgement such as my Methodist grandmother sought to inculcate. Add to this that Matthew, in chapter 13, provides us with a cascade of other, concurrent agricultural reflections in order to to help us to “tease the mind into active thought.” Matthew takes an already pungent parable and arranges it with similar parables to continue teasing out our understanding. There is plenty or room in this parable and its placement for making broader connections to guide our faith and practice from the master’s teaching. Besides a moralistic (even fatalistic) interpretation, what else is Jesus saying about the weeds and wheat in this parable?

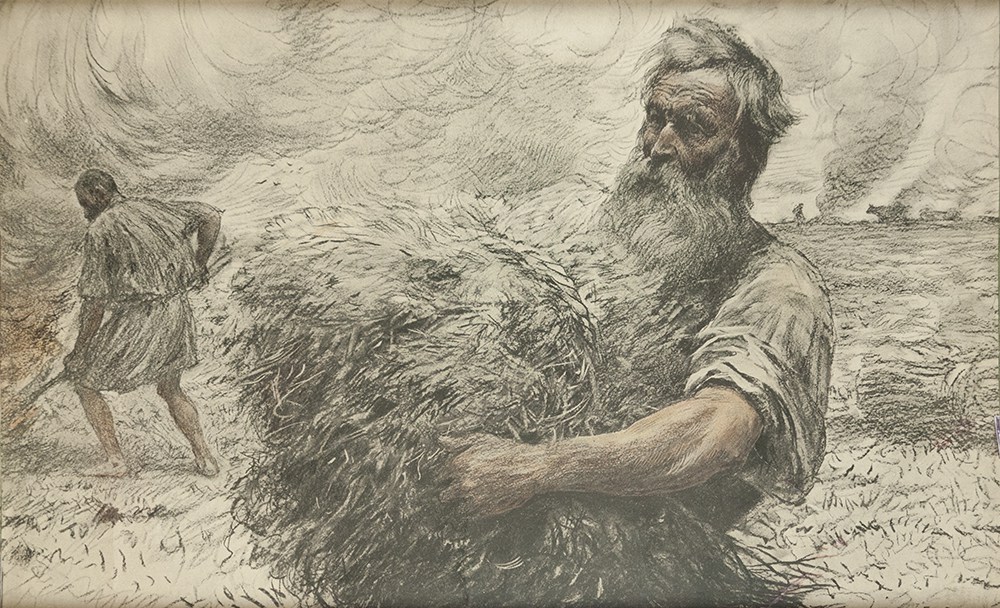

Entering into the parable of the weeds and the wheat with room to explore we discover in it one of the deepest human tendencies reflected back at us; even the one we’ve just been describing, the tendency to assign judgment and make assignments about who is a weed, who is wheat and what action we should take based on those judgements. Within the parable as Jesus is telling it we hear the cry go up from the servants, from those once the evil action is discovered, “Shall we pull the weeds?” they ask. “No, don’t pull.” The master replies. “Let them grow together.”

There was a weed called the darnel which was criminal to cast into a neighbor’s field. Since it was an illegal act listed in the law codes that means it was not an unknown act in the ancient world. The darnel weed, once discovered, could be pulled early and damage most of the real crop it was entangled with or pulled late, teased out but its pollen would poison the whole field of wheat. Either way it was a loss. Darnel was a dangerous, even criminal weed that would have filled the part of the common and natural story in the mind of Jesus’ hearers. But something is different at the end than what one would have expected. The wheat, though it has been allowed to grow, has not been poisoned at the end, but worthy of being gathered into the barn at the harvest.

Because we expect the worst we often follow our urge to action, to pull the weeds, to separate the good and the bad quickly. What Jesus says, though, as the master himself, is don’t pull, don’t follow the instinct to rip up even what the evil one has planted. One other note that adds to the strangeness and pungency of the parable of the weeds and wheat is how Matthew places this parable right before the parables of the mustard seed and then the leaven. Mustard seeds and leaven are foreign bodies to the field or dough they are introduced to. They take over the nature of what they’ve introduced to and change it’s character. In the analogies of the Kingdom of God here the mustard seed and the leaven operate not unlike the weeds. The small mustard seed takes over the field, the leaven makes the whole dough rise. Perhaps the master farmer’s advice not to pull the weeds is a broader reflection about how the weeds and the wheat operate in our soul and we must be careful about pulling what we are judging is evil.

If we look at this parable in concert with other parables and teachings in Matthew, we might even hear Jesus say to resist the urge to point out the speck in others because a log of weeds may be in our own..It may be, as other have rightly pointed out over the years, that the weeds and wheat are active and growing together inside each of us. We may actually be participating in kingdom work when we resist the urge to tear up what we see as weeds and let the master farmer guide the crop.

Resisting the urge to pull is not an easy one; leaving the harvest to the master takes patience and forbearance. It takes preaching peace and grace. Fortunately, that was something my grandmother minister could also do, quite gracefully.

The Rev. Matthew Cowden

Published in the Anglican Digest, Fall 2018